Working on Spielbound Teacher Guides

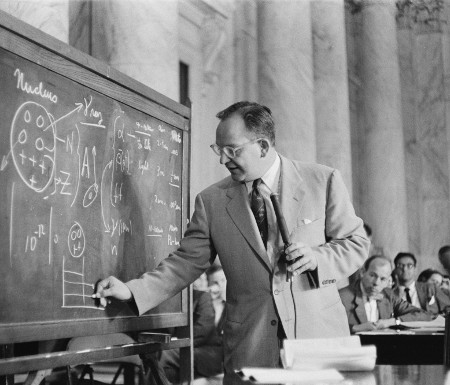

Submitted by Michael Fryda on Thu, 2016-07-14 10:28 Dr. Mark Mills drawing diagrams on a blackboard during testimony before the Congressional Joint Atomic Energy Committee hearings on atomic radioactive fallout, 1957. Hopefully integrating games into your curriculum isn't quite this complicated.

Dr. Mark Mills drawing diagrams on a blackboard during testimony before the Congressional Joint Atomic Energy Committee hearings on atomic radioactive fallout, 1957. Hopefully integrating games into your curriculum isn't quite this complicated.

Hello readers of Spielbound.org! The summer may be in full swing but that doesn’t mean that work stops for teachers. We’re participating in summer programs, working on strategic planning, and writing next year’s lessons! At Spielbound my goal for the summer is to start some serious work on getting some teacher guides going to help classroom teachers get the basic information they need to consider using existing games as part of their curriculum.

As I started this process, my biggest goal was to incorporate the realities of classroom teaching into a resource that would help an educator take the first steps into using games. I’ve spoken on this blog before about how logistics can be a challenge in the classroom. We have standards that we must meet. This doesn’t prevent us from innovating curriculum, but it means that we have to be very efficient in squeezing as much time as possible out of our available class time. For games, that means that any teacher guide that we produce at Spielbound needs to communicate how much time it could take students to have a great experience with a game. But that’s just a beginning.

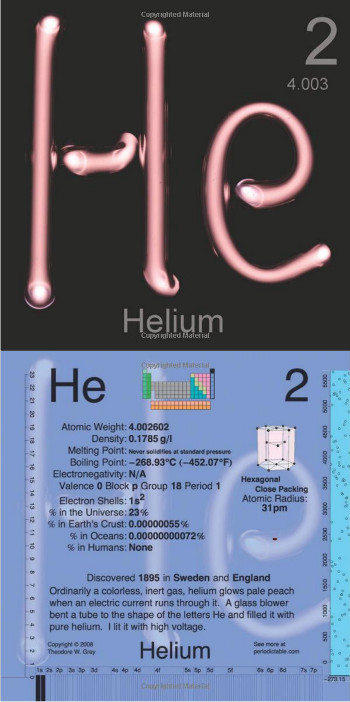

Helium as seen in Theo Gray’s The Photographic

Card Deck of the Elements. The top picture is top of the card, and the bottom picture is the "face" side of the

card.

Helium as seen in Theo Gray’s The Photographic

Card Deck of the Elements. The top picture is top of the card, and the bottom picture is the "face" side of the

card.

A traditional Battleship game.

A traditional Battleship game.

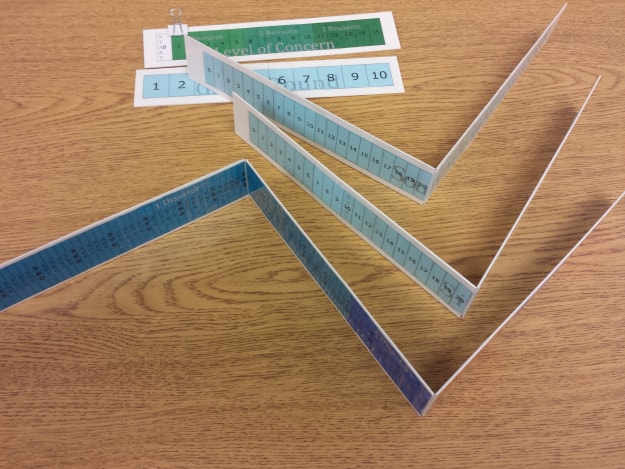

Prototype Meters for gameplay in the classroom.

Prototype Meters for gameplay in the classroom.